nationalism

noun

1.2 Advocacy of political independence for a particular country: Scottish nationalism

(From Oxford Dictionaries)

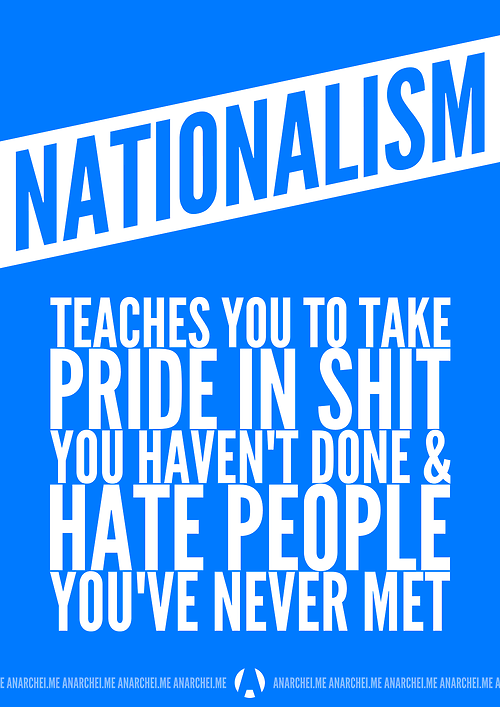

I wanted to start by writing that I hate nationalism, but I realised it isn’t true. I despise it. A long time ago I told some of the Venture Scouts in my Unit that nationalism was a cancer on the face of the planet. One of them kept repeating it back to me, like some sort of mantra which seemed to have no meaning to him. Hopefully here I can explain myself better.

Once up on a time there were no nations. People collecting into family groups, or tribes. As the world evolved it saw kingdoms, cities or city states, principalities and large tribal lands with the occasional empire rising and falling. Some lasted for a short time, some for longer. Borders were fluid, determined primarily by the latest battle, with geographical features only really mattering when they were prevented conquests. Nation States were really only defined in the Treaty of Westphalia in the 17th Century, though the model existed earlier in some places.

All nations, like many of the entities that went before them, self mythologised. Perhaps a hero pulled together disparate entities, freed a land from an oppressor or fulfilled a destiny by conquering a unjust leader. Whereas the truth was generally grubbier, with grabs for power or wealth often the main motivation. But it was the myth that was taught to its members. Sometimes we are appalled by this, for example when Japan produces its own self serving version of events in 1941-45, but all nations are guilty of this to some degree.

The desire to belong is strong in many people. A selfish gene type argument can easily explain this – in primitive human culture the primary grouping was essentially that of an extended family and supporting that group gave hope that your genes would survive and propagate further. It evolved in a time when supporting the group or not may mean life or death, to themselves and others.

But like many natural instincts, the emotion attaches itself to entities it didn’t originally evolve for. So over time it attached itself to tribes, cities, kings, races, nations and football clubs. Unfortunately this self identification creates problems. By identifying strongly with an entity, a person distinguishes themselves from others.

And this is my problem with nationalism. At its root is the favouritism of the people of one nation over all others, we are better than they are. There is something about the people of my nation that makes them different from everyone else, even if that difference is often ill defined, particularly once you get past language. And the mythologisation makes different mean better. At it’s heart is the denial of our common humanity – the statement of difference is exemplified by the synonyms given in the dictionary definition. It is no coincidence that many of the worst atrocities in history have been built on the back of nationalism, it is a framework which provides an easy context in which to frame hatred. Nationalism is racism without the illusion of genetics. It is a cancer on the face of the planet and it is time we cured it.

Scotland

I live in Edinburgh and, as I write, there is a vote next week on independence. From what I have written above you won’t be surprised to find I am voting no. I live in a liberal democracy with a strong economy, a fair rule of law and good social justice. Does it always work? No. Could we do better? Of course, but name me a country that couldn’t. As many people have shown, the Scots aren’t that different from the rest of Britain. I see people trying to magnify small or non-existent differences into huge chasms and I hate it.

I think the economics of independence stink too, but that is a whole other argument. Check my business blog for some comments on that.

So what’s the alternative?

What I think is missing from the debate (I’m guilty too) is asking at what level it is appropriate for something to be governed at. I should start that by saying that I have a lot of sympathy for the EU principle that things should be run at the lowest level that is appropriate, but that needs to be addressed on a case by case basis. To say Scotland is better running everything or the UK is better running everything is clearly stupid – no one level can be best for everything.

This is perhaps best illustrated by example:

Defence: as has been said elsewhere, we all live on the same bit of rock. Managing defence at a UK level seems appropriate, as the events of the last century or two show.

Education: through an accident of history Scotland has a different qualification system than the rest of the UK. That should be run at a Scottish level, which it is.

Health: having some sort of body (its called NICE) promoting best practice, drug authorisation etc at a national level seems good and spreading that over the largest number of people makes that cost effective (I know the cost of this bit isn’t huge, but its the principle I’m interested in.) Below that health services need to be delivered effectively at a local level. I’d suggest there is no reason that Scotland is the right level for that – it seems to me that the differences between the rural Highlands and urban Glasgow suggest that they need separate structures. Perhaps dividing Scotland into several parts might work best.

In other cases there are things that are best handled at a supra- national level. I believe some human rights are universal. I’d like to believe that of trade too, though the pragmatic side of me recognises that nationalist interests seem to prevent universally beneficial agreements (see how nationalism gets in the way of the common good?)

I realise that in a world that increasing appears to suffer from ADHD and looks for simple answers this isn’t it. But a considering the framework through this lens has to be way better than just saying because some people stick a label on themselves and say we are different1. In fact we already do it – it is just that what has happened so far seems to be almost by accident. It is time for a more considered approach.

1. For a more evidence based approach this paper for example looks at health and education in Wales & Scotland post devolution and actually concludes there is scant evidence of a ‘devolution dividend’.

One thought on “Nationalism”